|

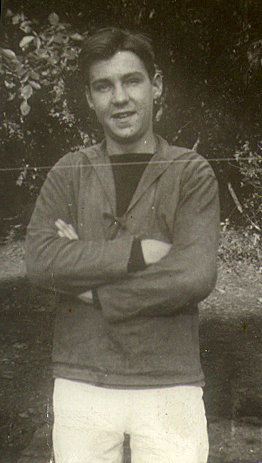

Matthew Mc Ginty

/back

A TRUE ACCOUNT OF MY LIFE AT SEA

DURING WORLD WAR TWO

By Matthew McGinty

I

was fourteen years old two months after the war started in September 1939.

Fourteen was then the minimum school leaving age. I

was fourteen years old two months after the war started in September 1939.

Fourteen was then the minimum school leaving age.

As a young lad I used to read every book I could find in the library that

had been written by old time sailing ship masters telling tales of sailing

the old windjammers round Cape Horn against the prevailing wind and other

such, what to me were daring adventures battling against the wind and

waves so when I finished school the only thing I wanted to be was a

sailor.

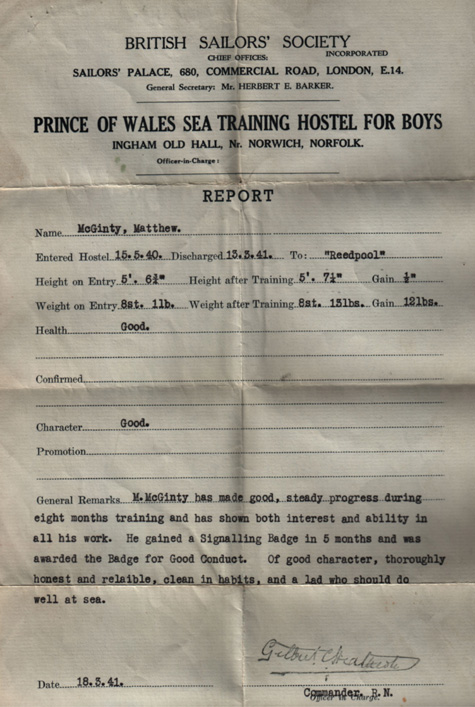

To this end my mother had found a place for me at the Prince of Wales Sea

Training Hostel run by the British Sailors Society (a religious

organisation that used to be in Limehouse, London but had been evacuated

to Ingham in Norfolk.

My three brothers and my sister all had to leave home at the age of

fourteen to get work, as there was none available in the north of England.

On the due day I was put on a train at Sunderland and told to change at

York and again at Peterborough for the local station. This was the first

time I had been out of the village on my own and even then I thought I

could manage without asking directions. Besides I was shy - scared is

maybe a better description.

As you might guess, I got on a wrong train and missed my connection,

finishing in Norwich with about two shillings to my name and the last

train of the day gone.

I told a policeman about my plight and he directed me to the YMCA where I

could get a bed for the night for one shilling then come back to continue

my journey on the next day.

When I did eventually arrive at the local station feeling lost and

forlorn, one of the staff phoned the Sea School to let them know I was

there and the chaplain came to pick me up and gave me a grilling about

where I had been all night.

The school was run on the style of the old Royal Navy training ships and

the instructors were ex-sailing ship petty officers. We had to be up at

six, washed, dressed and stood by our bunks (two high) with all our kit

laid out ready for inspection every morning.

We were all allocated areas of the building as our "Cleaning Station"

which could be the hall, the stairs, passage ways, toilets, officers

cabins (rooms), or any other place in the large building. We were changed

round each week so eventually we had a turn at everything. Also boys would

be detailed to help cook in the galley (kitchen) or wait on table in the

officer’s dining room. After kit inspection we would be called to cleaning

stations from seven am to breakfast time at eight am and again for an hour

in the evening.

During the rest of the day we were taught everything we would be likely to

need to know for a life at sea: knots and splicing of ropes and wires,

sewing and repairing sails, how to do stewards’ or cooks’ work, washing

and mending your own clothes, steering and all about the compass, general

seamanship, and lifeboat lowering and sailing, rules of the road at sea,

Morse code, semaphore and the international code of flags and other things

that I cannot recall for the moment.

Every Sunday we had to march three miles to the nearest village for church

parade. Life was very much regimented and only a couple of hours spread

over the day were you free to do your own thing. It was what I imagined

life would be like in an orphanage. Not a happy experience.

After spending nine months at the Prince of Wales Sea Training Hostel I

spent a couple of months in London waiting for a ship. I was staying at

“Jack’s Palace” run by the British Sailors’ Society on Commercial Road in

Limehouse.

Two of my brothers, Harry and Eddie, were working in London and came one

evening to take me to the cinema to see Charlie Chaplin in the Great

Dictator and while we were out there was an air raid. Next morning I was

called to the office and asked to explain where I was during the air raid,

as I should have asked permission to go off the premises on an evening.

About a week later my sister Grace who worked at the Bata shoe factory in

Grays in Essex, not too far away, came and took me out and I did not ask

permission as I had been told I would not get it on account of last time.

Once more there was an air raid. Next day I was again called to the office

and this time I was told that due to my bad behaviour I was to be sent to

North Shields. To them this was banishment. This was fine by me as I was

staying at the Seamen’s Mission and was able to go home to Marsden for

part of most days.

MY FIRST SHIP

I

signed on the S.S. Reedpool as a deck boy when I was fifteen. Captain

Downs said he knew my father but did not say how, and seemed to keep an

eye out for me because of this. Later I got to know that his nickname was

Back Breaker Downs. It seems that he started his seafaring life as a

seaman and put himself through Merchant Navy College to gain his

certificates. While he was a seaman he was involved in a fight and hit a

man with such force that he caused some harm to him, (not really a broken

back). From then on he was known as Back Breaker Downs. I

signed on the S.S. Reedpool as a deck boy when I was fifteen. Captain

Downs said he knew my father but did not say how, and seemed to keep an

eye out for me because of this. Later I got to know that his nickname was

Back Breaker Downs. It seems that he started his seafaring life as a

seaman and put himself through Merchant Navy College to gain his

certificates. While he was a seaman he was involved in a fight and hit a

man with such force that he caused some harm to him, (not really a broken

back). From then on he was known as Back Breaker Downs.

In those days we used to work four hours on and four hours off while at

sea. When we got home off the first trip the law governing working hours

had been changed so that foreign going seamen must have eight hours off

between watches. This was a much kinder way of working

The ship was loading coal at Dunston Staithes on the River Tyne for

Baltimore, Maryland on the Hudson River in the USA. On my second day on

board we moved down river to lie at anchor at Jarrow Slake ready to join a

coastal convoy. That night there was an air raid and the shrapnel from the

anti aircraft guns was falling onto the deck like hailstones.

When it was time to weigh the anchor we were unable to lift it because it

was fouled on something on the riverbed. Due to the time taken to try and

free the anchor (which we eventually slipped) when we finally got to sea

the convoy was away in the distance.

Weighing or lifting the anchor entailed the worst job I had to contend

with on the Reedpool. The ship was built in 1924 and to a tight budget so

it did not have a self-stowing chain locker. This meant when sailing from

an anchorage one of the able seamen (ABs) would be at the steering wheel,

the ships carpenter would operate the steam windlass, the boatswain would

hose the chain down to clean the mud etc from it. The first officer would

be in charge of the forecastle head crew, the other AB and the boy who

made up the remainder of the watch would have to dress in sea boots oil

skins and sou’westers and clamber down into the chain locker armed with a

chain hook each and as the chain was wound in they would have to pull it

out to the sides and corners of the chain locker. If it was allowed to

pile up in the centre it would eventually roll off the heap and if it

trapped you, the least you could get away with would be a broken leg. All

the while the water and foul smelling mud would be dripping down on you

and the chain would be slippery under foot. In cold climates you would be

freezing and in warm climates the sweat would be dripping off you.

Altogether a dreadful task.

When darkness fell and we were still some distance behind the convoy a

German aircraft flew over us and I helped the second officer to fire the

Oerlikon twenty millimetre anti-aircraft gun, situated on the wing of the

bridge, at the plane. This involved removing the gun cover and using a

wire strop to cock the gun. All very exciting. I was fighting the Germans!

The aircraft did not return fire so must have been after bigger fish. All

of this seemed to me to be a great adventure and I don’t remember any

feeling of fear, so my first week as a seaman was quite an eventful one.

We sailed along the coast and round the north of Scotland to Loch Long.

While at anchor in Loch Long awaiting a transatlantic convoy the boatswain

told two of the senior able seamen to get a coil of two and a half inch

wire from the store and splice a locking “eye splice” on the end of it to

be used as an insurance mooring wire. When he came back to see how they

were getting on he saw that they did not have a clue how to do a locking

splice. He shouted “McGinty! You and Harland went to that Sea School. Come

and splice this wire.”

For two fifteen year old lads it was like wrestling a wild animal, but we

managed to make a tidy successful job of it. For the rest of the voyage we

got clipped around the ear and kicked up the backside for every half or

invented excuse they could think of for showing them up. Boys had to keep

their place in those days.

When we arrived in Baltimore, where we spent a couple of weeks, I was

amazed as there was no war here and after several weeks of the cook’s good

solid bread, the pre-sliced bread (the first I had ever heard of) tasted

like cake. There was fresh milk and they used machines to unload the cargo

not men with shovels. They even put small bulldozers into the holds to

clear up. We had time ashore and everything was so different to wartime

Britain and girls seemed to like foreign sailors so we rather enjoyed

ourselves.

After unloading in the USA we went to Canada to load grain for home

loading at St John, New Brunswick and Sydney, Cape Breton then on to

Halifax, Nova Scotia to await a convoy for the UK. We set off across the

Atlantic a day or so before the battle to sink the Scharnhorst began. We

kept getting orders to sail south then north then every direction so as to

keep clear of the battle but still saw flashes and heard the sound of

distant gunfire. To me another great adventure.

We finally made it to the UK in 28 days instead of the expected 10 to14

days.

We then sailed up the Manchester Ship Canal to Salford Docks, which cannot

be done any more because ships are now too big and the docks are now a

leisure amenity.

After unloading our cargo of grain into a giant silo we went to Barry

Island, South Wales for minor repairs and improvements to our defence

arms. Since I joined the Reedpool the magnetic mine had been invented

which was triggered by the magnetic field around a ship. Ships were

beginning to be fitted with degaussing systems which helped to protect

vessels from these mines by neutralizing the magnetic field around the

ship.

Until this time we had had no electricity on board ship. One of my first

jobs was cleaning and filling the paraffin lamps. Meat and such was stored

in an ice room, which only kept it fit to eat for five days. After that we

lived on hard tack, the name given to salt preserved meat etc. As a result

of the generator, which was installed to power the degaussing system on

the Reedpool, we now got electric light and a refrigeration room, so from

then on we ate fresh (frozen) food for the full journey.

We then loaded coal for Buenos Aires, Argentina. To get to Argentina

involved crossing the equator, which after many years of tradition

required a ceremony involving King Neptune and his court. A makeshift

swimming pool had been constructed on the fore deck between No 1 hatch

cover and the side of the well deck. I was where I always seemed to be

when there was any activity, at the top of the foremast on lookout duty.

At the appointed time Neptune and his four assistants burst forth onto the

deck and formed a court on No 1 hatch near the pool. Neptune was Mr.

Lawson the first officer, his two chief court officials were the boatswain

and the ship’s carpenter who had made a two foot replica of an open razor,

and two big lads were policemen. They were all made up with long blond

hair made from rope strands, brown beards made out of teased out oakum and

grass skirts again made from rope strands.

Everybody on board who was not engaged on something essential was

assembled at various vantage points to watch the fun. I was kidding myself

that I would escape as I was on lookout and had a grandstand view of the

proceedings. The name of the first person to undergo the ordeal was called

out and two of Neptune’s men went to fetch him.

He was held firmly (with a little bit of theatrical struggling for effect)

and placed firmly on a chair near the pool. A charge was read out accusing

him of something or other. He was sentenced to be cleansed well within and

without, was given a shave with the wooden razor, had treacle poured over

his head, scrubbed all over with soft soap and a deck brush. Then he was

given a chocolate pill served off the biggest serving spoon out of the

galley. This pill was in fact a piece of soap coated in sugar and cocoa

powder.

He was told to bite the pill then tipped backwards into the pool. Then he

was washed down with the ship’s fire hose. This procedure was carried out

until all the first timers except me had been processed. Then to my dismay

the two Neptune attendants plus a relief man started to climb up the mast

ladder. There was to be no escape and I was ordered down the ladder to my

fate in Neptune’s court. I was charged with arson, “arson about the deck

all day” and given the standard sentence as described for the first

victim. After being given the shave, the treacle, the scrub and hose down,

I was told that I now had King Neptune’s permission to enter the Southern

Hemisphere as and when my duties required.

We were in Argentina for about five weeks as it was back to the manual

method of working cargo. I was able to learn a little Spanish which to my

amazement I could still remember some fifty years later when I took my

family to Spain for a holiday.

We had a good time in Buenos Aires as there was a good Seamen’s Mission

with a following of English ladies who organised day trips and the padre

took us to a football match in the gigantic football stadium there. We

were so far back off the pitch that we could hardly see the game.

We then sailed to Baja Blanca where we loaded grain, then on to Engineerio

White to complete the cargo with cowhides and maize.

From there we sailed for the west coast of South America (Peru) via the

Straits of Magellan taking on bunkers and stores at Montevideo, Uruguay,

en route. We had to take a pilot on board to take us through the narrows

toward the western end of the Strait and as we approached he personally

inspected all the steering equipment, sounded the ship’s whistle long and

loud then took the steering wheel himself and steered the ship through a

very narrow passage where the trees were brushing the sides of the ship.

We called at Valparaiso and Iquiqui, Chile for stores and bunkers on the

way north to Callao, Peru. While we were in Callao the first officer

organized a game of football between a local team of Brits and the ship’s

crew. I was pushed into the team against my wishes and we were beaten

twelve nil.

After leaving Callao we loaded nitrates, an ingredient in explosives,

while at anchor off two places Taltal and Lota. This we took to Egypt,

calling for stores and bunkers at Montevideo, Cape Town, and Lourenço

Marques, then we unloaded at anchor in the Great Bitter Lake.

Every lunchtime, the local stevedores would get out the hookahs and smoke

cannabis and when they went back to work they would rush like demons. One

afternoon when they were high after a good session they got careless and

managed to dislodge one of the hatch beams which fell some forty feet onto

several of the men loading the skips in the hold, killing them. Then there

was weeping and wailing as only Arabs know how.

We then spent some time trading back and forth between the Mediterranean

and Sudan via the Suez Canal. On one trip we ran aground then managed to

refloat ourselves but in the process damaged our rudder. We went to Port

Said for repairs and because this port was so busy with ships using the

canal all ships moored at right angles to the quay and everyone had to pay

for a boat to take them ashore and back when, if you were fit, you could

almost jump onto the quay.

One day there was an explosion at an ammunition store not far away. The

local workers did not hang about waiting for a boat to take them ashore

but were diving over the side like Olympic swimmers. We eventually got

orders to proceed to Trinidad to load a cargo for the U.K. This was to

prove easier said than done.

One day on the way south down the Red Sea a submarine was spotted running

on the surface parallel to us about half a mile off our port side.

Action stations were sounded and I took up my station as rammer on the

four inch gun. We were given the range calculation from the bridge and got

a round off. We did not miss by much but the sub did not return fire and

submerged.

There was many a discussion over the next few days as to why it did not

retaliate. Perhaps it was one of ours, or maybe they were out of

ammunition, or perhaps they thought we were their supply ship. I will

never know.

A few days after this we were caught in a typhoon. The waves were so bad

that one minute the front half of the ship was clear of the water and the

next it came crashing back down and the stern came clear leaving the

propeller free to thrash round causing the engine to almost shake the ship

apart.

This caused rivets to start (leak) and I was detailed to help the

carpenter to go down in the empty holds and make small shuttering round

the leaks then fill them with quick drying cement to hold the water out.

Through all of this I had no sense of fear, looking on it as a great

adventure (perhaps I just had no sense). In one twenty-four hour period we

were blown ten miles back from the position we were at the previous noon.

When the storm passed we had used up so much coal that we had to call at

the port of Mombasa in Kenya for more. There were several ships already at

anchor in this land-locked harbour waiting for coal. Each time a ship

would try to leave Lourenço Marques, Portuguese East Africa, to bring coal

to Mombasa it was torpedoed. After six weeks we had chipped off every bit

of rust and painted every inch of the ship that was out of the water

(sailors’ normal duties). We then spent our time lowering and raising

lifeboats, sailing round the harbour and ferrying the captain to another

Ropner ship, that was anchored there for the same reason as us, to

socialise with the captain. Good practice for what was to come.

After many weeks sailing, calling for stores and bunkers on the way, we

were in the Caribbean and I was on lookout at the masthead when I saw a

lifeboat in the distance.

This turned out to be from a ship called the Medon that had been sunk 36

days before. There were four survivors still alive. Two English and two

Chinese. One of the English men was a deck officer, the other a

refrigeration engineer.

THE SUBMARINE ATTACK

Six

days later I was again on lookout on the ‘noon till four’ watch when I

spotted and reported what I thought was a submarine periscope. The captain

and all the deck officers had just done the midday observations of the sun

to determine the ship’s position then gone down for lunch, leaving the

third mate in charge of the watch. He rang the alarm bell, which brought

all the deck officers, including the captain, rushing up from their lunch

to the bridge. After much searching and seeing nothing I was given dirty

looks and they all went back to a now cold lunch. A few moments later I

again saw and reported the periscope resulting in the same performance as

last time. Again, I was the only one to see the periscope, as the practice

was to raise the periscope, take a quick look then lower the periscope

again. The second officer came back on watch after his lunch break and I

reported the submarine twice more during my twelve to four watch but was

still the only person to have seen it. After I came off watch I passed the

first officer, a Mr Lawson, who tried to tell me that what I had seen was

the meeting of two opposing currents of water but I insisted that I had

clearly seen a periscope. Six

days later I was again on lookout on the ‘noon till four’ watch when I

spotted and reported what I thought was a submarine periscope. The captain

and all the deck officers had just done the midday observations of the sun

to determine the ship’s position then gone down for lunch, leaving the

third mate in charge of the watch. He rang the alarm bell, which brought

all the deck officers, including the captain, rushing up from their lunch

to the bridge. After much searching and seeing nothing I was given dirty

looks and they all went back to a now cold lunch. A few moments later I

again saw and reported the periscope resulting in the same performance as

last time. Again, I was the only one to see the periscope, as the practice

was to raise the periscope, take a quick look then lower the periscope

again. The second officer came back on watch after his lunch break and I

reported the submarine twice more during my twelve to four watch but was

still the only person to have seen it. After I came off watch I passed the

first officer, a Mr Lawson, who tried to tell me that what I had seen was

the meeting of two opposing currents of water but I insisted that I had

clearly seen a periscope.

That evening the captain made a tour of the ship making sure that no

lights were showing and told everyone that when it got properly dark he

would have the engine stopped for half an hour during which time there was

to be total silence. We would then start off in a different direction as

fast as it was possible to make the ship go, the idea being to fool the

submarine or outrun it. Everyone was more than happy to do this as our

only possible hope of escape.

I was on lookout on the forecastle head when the moon rose above the

horizon on the port side I started to scan the sea now there was a bit of

light. By the time I had scanned round to face forward there was a

terrific explosion possibly made louder by the fact that the ship was

empty and acting as a sound box? It was so loud that it temporarily numbed

my brain.

I turned to where the noise came from and saw a great column of water,

smoke and steam rising into the air from amidships on the starboard side.

When the moon started to rise over the horizon the submarine had been

placed so that we were a silhouette and a perfect target and a direct hit

was made into the engine room destroying the starboard lifeboat.

When I gathered my senses I realised that this was going to be a case of

abandon ship. As I was dressed in shorts a vest and sandals, I decided

that I would need some protection from the tropical sun if I survived till

next day. As my accommodation was just below my feet I jumped down to the

deck and ran to my cabin, grabbed a sheepskin lined leather jacket and a

hat and as an afterthought a carton of cigarettes.

I then made my way along the fore well deck toward the ladder on the

starboard side to get to my boat station but Captain Downs was stood at

the top of the ladder and said “Do not come up here son, there is a big

hole behind me. Go to the port side lifeboat.”

When I got to the foot of the ladder that led to the boat deck the

engineer’s mess boy ran up and said that Mr. Mustard the chief engineer

was trapped in his cabin. I was sent with one of the gunners and the mess

boy to help the engineer to escape from his cabin. We then helped him to a

liferaft. His hands and face were badly scalded.

By the time I eventually got to the boat deck there was only myself, the

two men that had lowered the boat and the captain left on board. The

captain told me to grab a rope and slide down into the boat. The two men

followed and finally came the captain. We rowed away from the sinking ship

and when we were a little way off the ship broke in half folding like a

jack knife with the bow lifting one way and the stern going the other.

There was then another explosion, which I imagined to be the boilers

blowing up as the cold seawater got to them.

The submarine, now on the surface, came towards the boat. There were a

couple of officers in the conning tower and two sailors stood on deck with

machine guns. We were a bit concerned about what was to happen next as we

had heard tales of Japanese subs shooting survivors in the water. We were

glad when we realised that this was a German U Boat. (I now know that this

was the U515 with ace German U-Boat commander Kapitänleutnant Werner Henke

in command. Henke was later to be decorated with the Knight’s Cross of the

Iron Cross in December 1942 and the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross on 4

July 1943.).

One of the officers asked if the master was in the boat. He said he was,

as we expected that they would go down the list to get the highest rank

available as proof of our sinking and to deprive the service of the most

valuable member of the crew. He was then invited ever so politely to “come

on board my submarine” which he did. We were then told to stand clear as

the sub was going to submerge. It moved off forward and down and was gone.

We passed the remainder of the night sorting ourselves out to make the

best use of the available space in the boat.

When daylight came we rowed to the raft that the chief engineer was on and

transferred him to the boat. By this time he was very ill. We took this

raft in tow and rowed to the other raft, which had several men on it. This

was the first time during the whole event that there had been anything

other than calm acceptance of our situation and orderly conduct. One of

the Canadian stokers tried to make a rush to get in the boat before

anybody else and one of the ABs floored him with a punch then all was calm

once more. We eventually got everybody into the boat.

Fortunately the weather was flat calm and had been so for several weeks,

otherwise due to the extent that the boat was overloaded we would have

been swamped. We spent the rest of the first day organising the boat and

arranging the rationing system and hoping for a little wind to sail the

boat.

Everyone was asked to hand in all cigarettes, rolling tobacco, cigarette

papers, matches and lighters for the common good of all survivors. It

seemed that everybody smoked those days and these were to be rationed

along with the food and water. There was no wind so we spent the day

relating our experiences of the sinking and hoping for rescue.

By the way, all of the crew’s wages stopped when the ship was sunk. There

is an entry in my discharge book stating that I was “Discharged at Sea Due

to Enemy Action”

One of the crew told how the second officer, who was on the bridge on

watch at the time of the explosion, had got into the lifeboat to make it

ready for lowering as this boat was assigned as his responsibility. He had

cleared the cover and was putting the drain plug in and shouted to someone

to release the slip that held the boat against the fenders that stopped it

banging about while at sea. This caused the boat to swing out then crash

back into the fender. As the boat swung out this caused the officer to

lose balance and fall between the boat and fender and when the boat swung

back it crushed the officer killing him instantly.

The engineer from the Medon said that he had been sleeping on the port

side pocket bunker hatch when the torpedo struck. This is a small hatch

about ten feet long and four feet wide. The explosion blew the hatch

covers up in the air along with him and he then fell into the bunker. The

inrush of water shot him back up again and this time he landed on the

deck. He was an extremely lucky man.

That night, after dark, we got excited as we could hear an aircraft engine

approaching. When it got close a distress flare was lit, but there was no

acknowledgement so we settled down again hoping we had been noticed.

Next day, Tuesday, there was a slight breeze so we set up the mast got the

sail up and made a little headway. The wind went down with the sun so we

lowered the sail but left the mast up for the next day. Once again we

heard an aircraft approaching and as it got near we lit another flare, but

still with no recognition.

We had the sail up again on Wednesday morning when we saw an aircraft low

in the sky circling some distance away. He then flew towards us, then back

to where he was circling, and someone said they must want us to go in that

direction. The oars were got out, and with the sail to help, we made good

progress and eventually got near enough to see the schooner Mini M Mosher,

a Dutch West Indian island trader.

We came alongside and were welcomed aboard by the master and his crew of

six quite young lads, maybe sixteen or seventeen years of age. It so

happened that this boat had been becalmed for some days and they were

getting short on food when they were saddled with about fifty plus of us.

The solution was to harpoon a couple of porpoise, which attracted sharks

to the bloodstained water. Several of these were caught and, as porpoise

was considered a delicacy and worth money, the shark were used to make a

rice and fish stew to feed the hungry hordes. I detested fish and every

time I got some anywhere near my mouth I retched, and could not eat to

save my life. I was offering my share of the stew to anybody who would

give me their ship’s biscuit in exchange.

We arrived at Georgetown, British Guiana on the Saturday, six days after

the sinking, and were welcomed by some official looking people. A big fuss

was made of us as the first British survivors to be landed there. In those

days everybody who was anybody in British Guiana was British. We were

taken to the YMCA and looked after by the lady volunteers.

Every day we were invited to one house for morning cocktails, another for

lunch, and yet another for afternoon drinks, and somewhere else for

evening dinner. We thought we had died and gone to heaven.

REPATRIATION

All good things must come to an end and thought was put into how we could

be repatriated.

The American Army Air Force had a base in the jungle up river from

Georgetown and with their cooperation it was decided that a few of us at a

time would be taken to the base. As room became available on a plane, we

would be flown to the States as a first step on our journey home. These

were the planes that had been over flying us when we were in the lifeboat.

We were all enjoying ourselves so much that none of us were keen to go

home yet. When we saw the American Army wagon coming toward us we were all

looking for ways to avoid being in the next group to go. Eventually I

could no longer escape and was taken on the wagon to the river and then

onto a launch.

We were taken up river for a two hours or more ride to the American base.

When we got there we were given a bunk and next morning we lined up for

breakfast, American style. That was some breakfast. It was more of the

same for all the other meals, no wonder there are so many large (fat)

people in the US.

After a short stay there was room on a plane. This was the first time I

had been up close to an aeroplane. It was a twin engine Dakota and was

stood on the runaway with its engines running, rattling and shaking and I

remember thinking I hope it does not fall apart when we are in it.

The seats were of the bench type running one down each side of the plane

as for parachutists. We were shown how to fasten our seat belts and were

off. When we had settled down one of the crew came round and told us that,

as it got dark, we would notice flames coming from the exhaust pipes. This

was normal and nothing to worry about. Not really very reassuring. Later

we were told that we would be stopping at Puerto Rico to refuel and asked

what sandwiches and drinks we would like to order for the rest of the

flight as there were no catering arrangements. We eventually arrived at

Miami, Florida and were booked in at a rather nice hotel.

Next step was to get to New York and we were put on a train on Sunday

evening for the journey. We were taken to the station where an enormous

steam locomotive stood at the head of a long train. I thought, this is the

USA, the most modern country in the world. This train will have us in New

York in no time at all. It set off at a walking pace through Miami and

miles of surrounding villages and hamlets and eventually got up to a

breathtaking 30 or 40 miles an hour in the open countryside. A local

stopping train in the UK travels much faster.

We finally got to New York at 10am on Wednesday after 60 hours travelling.

Fortunately we had sleeping compartments and all meals provided. On

arrival we were placed in a hotel in 49th Street not far from Times

Square, told to go to a certain restaurant for meals and report to the

Shipping Office each day to see if there was any ship wanting men.

I knew I had an uncle living in New York who used to be a sea going

engineer with one of the big passenger ship companies and was now a self

employed engineering advisor so I got the phone book out and looked up the

name Stephenson. I rang the first one on the list with that had the

correct initial and my aunt answered the phone!

I was given directions how to get there and told that I must come to see

them as soon as possible. There was Uncle Edward, Aunt Maggie, their

daughter Ruth and son Matthew. They had another son, Thomas, who lived in

England and was a sea going engineer.

For as long as I was in New York I spent every weekend with them and

enjoyed a party they put on for me on my 17th birthday on 13th November

1942.

HOME FOR CHRISTMAS

On December 3rd a man came from the shipping office and told me to collect

all my gear as I was to join the Norwegian tanker MT Norvinn as an

Ordinary Seaman and we would be sailing immediately. This ship had been

designated as the escort re-fuelling tanker and had special floating pipes

put on board for the job. About three days out we stood to on deck to give

one of the escorts fuel. We streamed the pipe out astern but the ship

could not pick it up, as the weather was too bad.

When the weather had settled down we tried again. This time they managed

to pick the pipe up then before any fuel was pumped they dropped it off

again because the Yanks had supplied the wrong connectors, giving us

American fittings, which would not fit British ships. That meant that the

escort had to leave us two at a time to go to Iceland for fuel leaving us

two escorts short as they took it in turns to go.

We arrived in Gourock on 23rd December 1942 and I was able to get home in

time for Christmas.

When I got home my three brothers and my sister were there. John, with his

wife Vera, Harry with his girlfriend Fay, my other brother Edward, and my

sister Grace. This was the first time we had all been in the same room

together for at least five years. We spent most of the night talking of

days gone by and the things we used to get up to as kids.

On the next working day I had to go to the Shipping Office to collect the

wages outstanding for me. When it was all added up and my holiday pay

included I had nearly £100. Nobody in our family had ever seen so much

money at one time. I came home, spread it out on the kitchen table and

felt like a millionaire!

I gave my mother a lump sum (I forget how much) and put the rest in the

bank.

I bought myself a piano accordion with some of my money. I could pick a

tune with one finger on the piano part of the accordion but could not make

head or tail of the left hand buttons. My father used to be a brass band

musician in his younger days but said he did not understand it any more

than I did, and anyway he could “make a better sound with his arse”.

When I left home as a fourteen year old I did not smoke. When I got home I

had been a smoker or a long time and got a cigarette out and lit up. Much

to my surprise I was then given the lecture of a lifetime from my Father

who was a pipe smoker. He called me every kind of fool he could lay tongue

to. Having got that off his chest he looked at the clock and said “They’re

open. I’ll take you for a pint”, even though I was under age and he had

just been telling me off for smoking.

After enjoying my due leave and spending some time on the register

awaiting a job on a ship, myself and three others were given rail passes

and sent to Southampton where we were given passes to board the SS

Caernarfon Castle to see the first officer about joining his crew. He took

one look at us and said “I want no North Sea Chinamen on my ship”, then

signed our passes to say we had applied for work and been refused. We were

then able to report back to the shipping office where we were given rail

passes home again

BACK TO SEA

On the 26th of February 1943 I joined the Chertsey, (an Empire Boat) which

was brand new and being fitted out at Pickersgill’s shipyard on the river

Wear. In due course we took her out on sea trials, tested turning circles,

time taken from full ahead to stop and going astern, did speed trials over

the measured mile and every manoeuvre in the book, then adjusted compasses

and finally the ship was handed over to the new owners.

We then sailed to St Johns, Nova Scotia, having joined a convoy from Loch

Long in Scotland. Except for the sound of depth charges being dropped by

the escort in the distance outside the convoy and the occasional enemy

aircraft being chased off by our air cover we had an uneventful trip. We

loaded grain and timber then sailed to Halifax to await a convoy back

home.

We joined a coastal convoy off the Scottish coast and sailed round to the

mouth to the river Humber prior to docking at Hull. As my father was now a

pensioner, and not well off to say the least, I decided to buy him a pound

of pipe tobacco. We were then told that HM Customs were coming aboard to

make a detailed search and I did not intend to pay duty on a pound of

tobacco so I put on my full length sea boots and stuffed the tobacco half

into each boot and walked around like that. This was in May1943 and the

weather was extra warm so if Customs had come on board it would have been

obvious I was up to something with my thick woollen socks and sea boots

on.

As things turned out they never came near and I was able to see the look

on my Dad’s face on being presented with a pound of pipe tobacco.

The natural thing to do when one completed a voyage at this stage during

the war was to sign off the ship and take whatever leave was due then

joins the seamen’s pool to wait for your next ship. The feeling was that

you had survived one trip and you may not be so fortunate if you made

another trip on the same vessel.

My next ship was a coastal collier called the Corbridge.

This was another “pier head jump” and though I was neither old enough nor

did I have enough sea time in to qualify I was signed on as an Able

Seaman.

Life was totally different on a coastal collier. When in a northern port

half of the crew went home and the other half worked the ship as and when

required without regard to the hours worked. Next time north, the roles

were changed and it was the turn of the other half of the crew.

In the port of discharge, (usually one of the London power stations or gas

works) you moored the ship and did normal work until midday then were free

to do your own thing. While at sea you worked four hours on and four hours

off and washed your clothes and kept your accommodation clean and cooked

and ate your food in your own time, which did not leave much time for

sleep.

The amount of rations we were given was much more than a normal civilian.

The reason given was that we had no works canteen to go to, nor could we

go to the local British Restaurant or fish and chip shop while at sea. It

was embarrassing to go into a butcher’s shop and get a whole leg of lamb

off one ration book when the harassed housewife behind you in the queue

could only have a few chops for the whole family. We were also allowed

much more sugar, butter, tea, eggs, cooking fat etc.

Life was hard on the coastal colliers. There was the constant danger of

shipwreck during storms while near the rocks, also minefields, submarines,

enemy aircraft and E Boats to contend with and when you got “safely” into

the Thames there were mass air raids.

On one of our trips north we carried bales of wool to unload at Hull. My

brother John lived in Hull at that time with his wife and family. He

worked for the Admiralty. When I visited him he was supervising the

fitting of Asdic submarine detection devices into converted trawlers which

the Navy were use as escort vessels. I went to his house and was able to

give him some of my spare rations. It was a treat just to see them

enjoying bread and best butter.

I survived six months of this without being sunk or injured and went to

sign a new six months contract when the eagle eyed shipping officer in the

Sunderland shipping office spotted that I was not old enough to be an able

seaman and even though I had done the job to everybody’s satisfaction for

the last six months I was given one day’s pay for my trouble and paid off.

As was now the norm, I took my leave then joined the seamen’s pool.

THE RUSSIAN TRIP

On the 2nd March 1943 I signed on the Fort Kullyspell which was loading at

the Corporation Quay, Sunderland for a trip to Russia.

The boatswain was a man called Alf Horabin and had just finished his leave

off his last trip, which was to Russia. He told us that he had been sunk

and rescued twice on the way there, and the ship he eventually got to

Russia on was then bombed and sunk alongside the quay. Hardly the kind of

story to fill us with confidence for our forthcoming trip!

We were taking on a mixed cargo, which included a complete factory right

down to two enormous boilers as deck cargo, for which we were fitted with

two fifty-ton heavy lifting derricks as there would be no dockside

facilities to handle such weight. Also we had wines, spirits, cigars and

cigarettes for British officers who were stationed in Russia. We took on

depth charges as well as a variety of other munitions (but no torpedoes)

to supply the escort vessels at some point during the trip. When we did

sail we took two male and two female R.A.F. officers with us.

When loading was completed we joined a coastal convoy to Loch Ewe where we

waited until an enormous convoy of one hundred and four merchant ships had

assembled. The escort included two cruisers, two “Woolworth” carriers (US

built oil tankers with flight decks built over the normal decks) and

twenty or more destroyers and corvettes. We set off north into a raging

sea on March 27th.

On the 1st April one of the lads shouted down from the deck “Come and see

this aircraft that has crashed into the stern of the carrier”. Being April

Fool’s day we were reluctant to believe him but when we did go on deck

there was a Fairey Swordfish sticking out of the gap between the flight

deck and the normal deck of the carrier that was stationed in the next

column and two ships ahead of us. As I mentioned, we were driving head on

into a very rough sea and the pilot must have misjudged the rise and fall

of the ship and flew his plane into the stern of the carrier.

The next day, with the storm still raging another aircraft from the same

ship failed to gain enough speed for take off and flopped over the front

of the flight deck and was ploughed under by the ship.

We could hear the sound of depth charges being dropped and the escort

vessels dashing about at top speed and the planes from the carriers flying

about, but otherwise were not aware of any other casualties except the two

unfortunate pilots. The stretch of sea between Bear Island and Norway was

the most dangerous part of the trip as there was a limited amount of sea

room and we were within range of German aircraft stationed in Norway. By

this time it was so cold that the sea spray that swept the ship froze

almost instantly and we were kept busy chipping ice off ropes and tackle

and other vital equipment but we made it to Murmansk without losing any

ships.

I have since learned from the internet that 3 German submarines were sunk

on the outward trip and 4 more on the return voyage.

When we arrived at Murmansk, customs, immigration officials and the port

doctor came on board. This was all very normal except that the doctor was

a woman. As was usual the ships crew had to line up for a medical which

always involved dropping one’s trousers for V.D. inspection and quite a

few of us younger ones were more than a bit embarrassed. A series of

notices were posted in every mess room stating that “ANY PERSON CAUGHT

GIVING, SELLING, OR EXCHANGING ANYTHING WITH A RUSSIAN WILL BE SENT FOR

FIVE YEARS HARD LABOUR IN SIBERIA”.

While we were at anchor in Murmansk a destroyer came alongside to take the

depth charges and other munitions we had for them. I was leaning over the

rail talking to one of the crew when he asked me where I came from. I said

“you will never have heard of the place” but he insisted, saying that

there were two hundred men in the crew and one of them might even know me.

This turned out to be a fact as one of the crew lived in the next street

to me. A chap a little older than me whose nickname back home was Gunner

Wells.

We had to wait for an ice pilot and two icebreaker ships to take us

through the White Sea to Archangel. The hull of these ships was designed

so that as the ship drove at the ice it would ride up onto the ice and the

weight of the ship would break it. One of the icebreakers took the lead

and we had to follow close behind. Then another Russian ship that was to

act as a warehouse for some of our cargo joined us, and the second

icebreaker was churning about making sure that nobody became stuck in the

ice.

We had to sail on to a place called Economia, which was only open for a

short time each summer due to the sea freezing over so thick. To give you

some idea, the ice was as much as ten feet thick in places. When we got

into the river leading to our port of discharge, because it was freshwater

it was re-freezing much quicker than the sea did. By the time the ship had

gone two or three hundred yards, people were able to cross where we had

been.

We were now a matter of fifty feet or so from the quay, but with quite

thick ice between us and the quayside, it was to be a bit of a problem to

get alongside. With the ship heading upstream, we got a head rope onto a

bollard forward of the bows and applied some tension to it using the

windlass. At the same time men were pushing blocks of ice away towards the

stern using long poles. This process took a couple of hours.

While this was going on we saw a young boy on the ice on the offside of

the ship. Feeling sorry for the lad, someone threw him a loaf of bread. As

soon as he picked it up, a soldier collared him and made him climb up onto

the quay, where he was made to march up and down until we got alongside

and got a gangway down. He was then take to the ship’s office where the

authorities asked the captain to charging him with stealing. I think he

told them to get lost.

When we had the ship safely moored we got dressed up in our going ashore

clothes and presented ourselves to the ship’s office for an advance on our

wages and shore leave passes.

We were told that the generous Russian government was giving us 200

Roubles each for bringing supplies to Russia, but when we left we were not

to take any Russian money that we might have left. There was nothing to

spend money on except the ONE glass of Vodka that you were allowed to

purchase on any one day, so when we sailed most of us handed back about

150 Roubles.

We were given our passes, which were written entirely in Russian, so none

of us had a clue what they said. We set off to go ashore and when I got to

the bottom of the gangway the Russian sentry indicated that he wanted to

see my pass. When I showed him he immediately took his rifle off his

shoulder, pointed it at me and waved me back onto the ship. Back I went to

the ship’s office where the interpreter said I had been given the wrong

pass and changed it for the right one. I went back to the gangway to join

the rest of the lads, but as soon as I put my foot on the first step the

sentry had his rifle pointing at me, so I had to wait until they changed

sentries before I could go ashore.

I had not missed much. The quay had rail tracks on it, but no rolling

stock. Most of the cargo was loaded onto metal plates, which were used as

sledges and dragged over the snow by tractors. Out on the streets there

was about eight or ten feet of snow piled up on either side of the road,

but the trams were still running. When we got to the town there was a

couple of shops with nothing in them and one hotel run by the Tourist

Board which was where you could buy your one drink per day.

Next day was the first full working day in port and, first thing in the

morning, a bunch of men and boys were marched under guard to the ship. It

appeared that they were political prisoners and were to do any labouring

work needed. All other jobs, for example crane driving, winch operating,

slinging, and signalling to the crane drivers, was done by women. The

Russian ship that came with us from Archangel was tied up on the offside

of us. Two of the ABs were women and they looked more like men than the

men did. Various bits of our cargo were transferred to this ship and the

two large boilers were loaded onto its deck.

On the night before the Russian was due to leave us, two of the crew who

could speak English came over to our mess room, as we thought to say bon

voyage. We sat talking long into the night and they finally left. We were

due to sail the following evening and as part of the preparations for

sailing all fresh water and rations were checked in the lifeboats and

rafts. We found that all the rations had vanished from the boats and rafts

and the only people we could blame were the Russians. Evidently the

friendly chat was a diversion while they robbed the boats. Stealing

supplies from a lifeboat was considered to be the most lowlife trick

possible during the war. Worse than stealing from your best mate or even

committing murder.

We were able to make our way back to Murmansk without the aid of

icebreakers as the ice had been thawing all the time we had been there. We

did pass one or two fields of ice but where the master thought the it was

thin enough we would force our way through it and if he had doubts we

sailed around the ice. With driving through the ice, the bows at the

waterline were polished almost like silver where the ice had rubbed along

the metal. We assembled in Murmansk to make another big convoy of 54

merchant ships and a similar escort as we had on the way there. Most of

the ships were American and I think all of the gunners must have been wild

west cowboys before the war as they were all trigger happy.

On the way home, when we got to the notorious area between Bear Island and

Norway, all hell broke loose. Escort vessels were charging up and down

between the columns of merchantmen dropping depth charges dangerously

close to us. When one went off right alongside of us one poor chap got

into a panic. He had been sleeping on his bunk during his watch off with

all his clothes on and his belt loose for comfort (as we all did while at

sea due to the constant danger of being sunk at any time without warning).

He must have thought that we had been hit due to the loudness of the

explosion and came struggling up the companionway with his trousers

falling down to his knees. He would have been much quicker to have stopped

and secured his pants.

A signal was sent from the commodore to all ships saying that submarines

had got inside the convoy and all gunners were to fire at anything that

looked like periscopes to alert the escort. As I said earlier all the

Yanks must have been cowboys and this was just what they had been longing

for. They let blaze at everything that broke the water not caring what

they might hit as a consequence and as there was a decent breeze blowing

there were white wave crests everywhere. There were bullets and

twenty-millimetre shells flying everywhere, even through the rigging of

the ships next to them. No wonder the Americans kill so many of their own

and allied service men. After the commodore saw what was going on he sent

another signal to all ships saying all merchantmen were to cease fire and

leave the job to the escort as they were killing all the fish. Two

merchant ships were sunk during this attack but I do not know how many of

the enemy were sunk.

When we got back home we found out that two ships in our convoy were

carrying 200 Russian sailors each who were to man two world war one

destroyers that had been given to Russia under the Lease Lend scheme. They

were the only two ships out of over 100 in the convoy that had been sunk.

This showed the importance of the slogan “Even the walls have ears”, as

somebody must have known which ships to concentrate on during the attack.

SPECIAL OPERATIONS

I signed off this ship in Glasgow on 11th May 1944 in line with my one

ship, one trip policy and was told “you can sign on for another trip to

Russia or volunteer for Special Operations, the Liberation of Europe”. I

chose Special Operations. While I was on leave I took the Efficient Deck

Hand’s examination and was now entitled to a full Able Seaman’s pay on any

future ship even though I was still two years too young, and had not

served enough time to be an AB.

After the short leave that I was due I signed on the Fort Findlay on 19th

May 1944.

The ship was at one of the fitting out berths on the River Wear, being

prepared for carrying troops and their vehicles. Securing points with

rings and chains with quick release gear were being fitted on the bottom

of the main hold and makeshift living/sleeping accommodation was being

built into the between deck area. On the main deck, long sheds were built

alongside the rails on each side of the ship. In these sheds were troughs

the length of the shed with a cover over them. In the covers were openings

the size of toilet seats. A water pipe was fitted to the fore end of the

trough which was higher than the after end, to which was fitted a

discharge pipe. What we now had were water toilets similar to those the

Romans used all those years ago in their forts along the Roman Wall.

When all of this work was done we sailed up the coast to Loch Ewe where a

large number of ships with escort vessels were assembled. Each morning we

would set sail in two columns with escort. Sometimes we headed toward

Norway and returned to our anchorage after dark. The next day we would

head off in a different direction. We guessed that this was to confuse

Jerry about where and when the attack on Europe was to take place and from

which direction.

This went on until June 5th when we headed south and kept going. As we

were passing what we judged to be the Humber we got news that troops had

landed in Normandy. We proceeded south to Tilbury Docks on the Thames

where we took on personnel carriers, army trucks and the soldiers that

went with them, and set sail for the beachhead.

It was common practice to wash the ship down from stem to stern with power

hoses as we left port, to get rid of all the muck and rubbish that had

accumulated. Lots of the soldiers were leaning over the rails being sick,

and sometimes it was necessary to ask them to move or they would get

soaked, but they were too ill to care.

We passed through the Straits of Dover during the hours of daylight so we

had to make a smokescreen to spoil the aim of the big guns at Calais. They

fired some shells but did not hit anything. I was on midnight to four am

watch and by then we could hear the sound of guns and bombs so I told

myself that I must get some sleep as this might be my last chance.

I awoke with a start when the ship’s engine stopped and the anchor chain

rattled out as we came to our allotted anchorage at the Juno beachhead. It

was nine o’clock on the eighth of June and beautiful morning with a flat

calm sea. I looked out of the porthole and there were ships as far as the

eye could see in every direction. I did not imagine that there were so

many ships in the world. All was quiet until about midday when a plane

tried to attack the ships but it did not get close, as there were fighter

planes after it immediately.

Within an hour or so of arriving, barges started to come alongside and

Royal Engineer stevedores came aboard. They transferred the vehicles to

the barges and their drivers etc clambered down scramble nets. Some of the

lads were so sea sick that they would have gone to any lengths just to get

off the ship.

There were three large warships laying a bit further off shore than the

merchant ships and every now and then they would open up with a barrage

from their big guns. I guess this would be at the request of some officer

in the front line. We would see the flash from the gun barrels then hear

the swoosh of the shells flying over our heads and then the thump of the

shells landing beyond our sight and hopefully on target. We were unloaded

by six o’clock and set off for the Thames to pick up another load.

While we were making repeated return trips to the Thames, Hitler was

making his last desperate attempt to turn the tide of the war with his

secret weapons the V1 and the V2

The V1 flying bomb or Doodlebug as it was named used to make a strange

sound as it flew and when the noise stopped there would be a few seconds

silence followed by a terrific explosion of the one ton bomb going off.

When you noticed the sound stop you would dive for cover and hold your

breath until you heard the bang, then you could breathe again.

The V2 was even worse as you had no warning of its approach and it had a

six ton warhead. Fortunately I did not experience the V2. Both these

weapons were designed to frighten people into submission as well as for

their destructive power.

Perhaps the most upsetting thing about the whole war was to see the

occasional body floating past when we were at the beachhead and not be

able to do anything about it.

We did several round trips in quick succession going to various

beachheads. On one return trip, instead of going to the Thames we went to

Southampton where we picked up a load of Americans and took them to Omaha

beachhead. They were swapping American army field rations for our cook’s

hand made bread. We on the other hand, thought their KP rations were

better than the food we were getting.

On the way over we passed two tugs towing what looked like a giant cable

drum. They turned out to be laying the famous Pluto pipeline that was to

supply the allied forces with fuel. We also passed numerous tugs towing

huge floating concrete blocks which were towed into place at the beachhead

then sunk to form a jetty to make the landing of troops and equipment

easier and quicker.

This shuttle service went on until the army had secured the port of

Cherbourg and our forces were well established on the continent. We were

now surplus to requirement so were sent to Glasgow where the ship was to

be restored for its normal trade. I signed off on 27th September 1944

having made 16 trips to the beachheads.

BACK ON CARGO SHIPS

After taking my due leave I joined the Empire Cowdray on 23rd October

1944. This was a new ship still being fitted out at Doxfords Shipyard. We

were moored three ships abreast. At this time my brother Edward was

working as an electrician at the yard and he came aboard and I showed him

around. While he was on board one of the adjacent ships was taken away. As

we stood on the deck, Edward got the impression that it was our ship that

was sailing and was worried about getting ashore until I assured him that

it was not we who were moving.

Eventually the ship was deemed ready and we sailed out of the river to do

two days of Acceptance Trials with a number of men from the shipyard doing

various finishing off jobs.

We steamed up and down the measured mile, did high speed turns, full

ahead, full astern and various other manoeuvres, then adjusted compasses

and returned to port to load.

We berthed at the staithes in Hendon Docks and loaded coal for Baltimore

in the USA.

The crew was made up of almost entirely Sunderland men, two of whom lived

in Hendon. When loading was complete we had about two hours to spare

before we needed to set sail to met the coastal convoy as it passed the

mouth of the river. We were told we could go ashore for a quick one before

we sailed, but must be back on board ready to sail at one pm.

Almost the entire crew went to a pub on the dockside within sight of the

ship. The mother of one of the lads was in there and it did not take long

to get a few down. When one o’clock came, somebody made a move to go but

was encouraged to sit down and have another. Then the master blew the

signal letter P on the ship’s whistle, which means “I am about to sail”.

It was so close that you could feel the vibration through your seat. The

lad who was sat with his mother, Nobby Clarke said “If we all stick

together they’ll do nothing about us not going on board”.

Next an officer apprentice was sent to the pub to tell us that we were

required on board immediately, but he was shouted down and invited to have

a drink with us. The poor lad had to admit defeat and returned to the

ship. Finally the first officer came and told us to get back on board or

he would have us all put in jail. We rolled back to the ship much the

worse for wear and now it was too late and we were too drunk to sail to

meet the convoy.

We were given a few hours to sober up, then called to the master’s office.

We were told that we were to be entered in the ship’s log book as having

refused the lawful command of the master thereby causing the ship to miss

a convoy, and fined accordingly. We got away the next day and sailed round

to one of the Scottish lochs then joined a transatlantic convoy.

After unloading at Baltimore we went to Philadelphia and took on a cargo

of grain topped off with aeroplanes crated up as deck cargo. Then we set

sail for Cagliari in Sardinia and about half way through the trip we were

overtaken by a considerable storm. The wind and waves were coming from

astern, which eased things a little. The waves were so big that they

lifted the stern, pushing us along like a surfboard.

One day during this storm I was on the four till eight watch as lookout,

but as normal during bad weather I was on the bridge with the officer as

it was too bad to climb the mast. At this stage during the war, the German

Navy had been hounded into port by the allied Navies and we did not

maintain such a strict lookout during the daytime.

It was usual for the lookout man to join the boatswain working on deck

when daylight arrived. When I had not been sent down by seven o’clock, the

usual starting time, I asked the officer when he was going to send me

down. He asked what I thought I could do on deck in this weather.

I was a bit fed up with being kept on lookout and was looking aft when a

larger than usual roller broke over our stern. To my horror I saw that one

of the DEMS gunners was on his way along the deck from his accommodation

in the after housing to the galley amidships to collect breakfast for the

gunnery crew. The whole of the after deck disappeared under the mass of

water that swept on board and the gunner vanished from sight. I was

certain that he was a goner. It turned out that had been swept along the

deck to the galley entrance (which had a little blackout screen around it

to stop light showing after dark) then into the galley where the cooks,

the galley boy and he were swimming around with all the pans and

everybody’s breakfast. There was no hot breakfast that day.

We eventually got to Sardinia and were the first ship to dock since the

Germans left. They had scuttled ships in the harbour entrance, destroyed

all the cranes and taken all motor transport with them. The water was so

clear that we could see the bottom of the harbour and were able to inch

our way around the wrecks. We unloaded the ship using our derricks. The

cargo was taken away by horse and cart, which made it a long drawn out

job.

For the rest of the voyage Nobby Clarke and myself were put onto day work

as opposed to watch keeping, as we were considered the most capable at

jobs like wire and rope splicing, rigging tackle and maintaining block and

tackles, and so of more help to the boatswain.

From Sardinia we went to Casablanca, Port Said and through the Suez Canal

to Port Sudan where we loaded maize, cottonseed and various other things

for Madras and Calcutta.

While we were sailing between Madras and Calcutta the war in Europe ended,

but it did not mean as much to us as you would expect as we were sailing

in waters that were in reach of the Japanese Navy. There was a very muted

celebration and no getting drunk, as lowly seamen were not allowed strong

drink at sea.

During the trip to India, Clarke and I were asked to oil the wire stays on

the mainmast and to paint the mast and derricks as a “job and finish” as

it was a dirty job working in the fumes being blown aft from the funnel.

We were finished and all the gear put away by noon.

Next day we were asked to do the same job on the foremast but this time it

would not be “job and finish”, the reason being that we were not working

in the fumes. Nobby said we would not do it unless it was a “job and

finish” and I was asked and naturally stuck by Nobby. All this was brought

to the attention of the first officer who told me not to be led astray by

Clarke, as he would get me into trouble. Eventually we were persuaded to

get on with the job and we spun it out until four thirty, giving just time

to get cleaned up for finishing time so neither side won the argument.

While in Calcutta we were at the swimming pool attached to the Seamen’s

Mission and I was sat on the side when someone said “get yourself in”. I

said I could not swim, but no one believed me and they pushed me in. I

really could not swim and when I shouted for help they thought I was

messing about. I managed to get to the side and from then on made a

determined effort to learn to swim at which I eventually became reasonably

proficient.

We started the return voyage, and on the way called at Bombay. There was a

road about a mile long leading from the docks to the town. Along this

road, were all manner of professional beggars, some with no arms, some

with no legs, some with neither arms or legs, some blind, mothers with

nursing babies, orphans, and so the list goes on.

There were also many tradesmen. You could get a shave and haircut followed

by a steam face towel, have a suit made to measure, some hand made shirts,

a pair of hand made boots or shoes made to measure etc. I asked for a pair

of leather sandals and was told to put my foot onto a sheet of leather. A

line was drawn round my foot and the same was done with my other foot. The

man said “come back in one hour” and when I did, I got the best pair of

sandals I have ever had for what was a very few shillings and they lasted

many years.

We left Bombay to sail for home via Lourenço Marques, the Suez Canal and

Gibraltar.

While we were on passage from Bombay to Lourenço Marques I had a painful

abscess in my left ear for which I was given M&B tablets (named after the

manufacturer, May & Baker) as there were no antibiotics in those days. At

this time V.J. Day was declared on 15th August 1945 and at last we could

all relax and go to sleep with reasonable hopes of not being sunk except

by mines (of which both we and the Germans had placed many), or natural

disaster. All the minefields were well charted, but sometimes a stray mine

broke adrift (and they still do to this day) and a lookout had to be kept

to avoid them. On VJ Day the Master really let himself go and issued each

man with a half-pint bottle of lager to celebrate the end of hostilities.

We were now on our way home but called at Gibraltar to take on fuel fresh

water and stores and as usual we were all put on day work. We had started

at seven am doing the various jobs as ordered by the boatswain then

stopped for breakfast at eight. On this occasion breakfast was liver and

bacon with mashed potatoes. It was some time since we had last taken on

fresh stores and Nobby Clarke decided that the liver was off.

He told me, being the youngest, to go back to the Cook and tell him that

the food was off and to ask for something else. Cook said there was

nothing else to give us, so when the boatswain came to tell us to start

work again Clarke said we were not starting as we had no breakfast. The

Chief steward then offered us some cornflakes, which were laughed at. Next

the first officer came and said that we were committing mutiny on the high

seas for which there was a prison sentence. Big mouth Clark said we were

not on the high seas but in a safe anchorage so were not committing

mutiny. We were then told to assemble below the master’s veranda where he

asked what the trouble was, and after some discussion Cook was told to fix

us something to eat and we eventually got back to work.

The procedure immediately before sailing on every occasion was for the man

whose turn it was to steer, to be ordered to try the wheel hard over to

port then to starboard and report to the officer whether the rudder had

moved as shown on the indicator. On this particular occasion the greaser

from the engineer’s department was in the steering machine house as this

manoeuvre was carried out. Somehow he got his upper arm caught in the

mechanism and had a chunk ripped out of his arm. The first aid officer put

a tight bandage on to stop him from bleeding to death and a doctor was

sent for to escort him ashore in a fast launch.

We then sailed for home, South Shields on this occasion, which was just

four miles from my home in Whitburn. I signed off on the 15th October

1945, but even though the war was over I was not allowed to leave the

Merchant Navy, a civilian occupation, as though I had been a member the

armed forces.

THE COASTAL COLLIER

On 14th November 1945, the day after my 20th birthday, I signed on my next

ship, the Sir David, a coastal collier designed to sail under the bridges

on the river Thames, and commonly known as a Flat Iron. There was little

or no superstructure and the bridge was just above the amidships

accommodation. When sailing fully loaded there was very little freeboard

and in rough weather it was nearly like sailing on a submarine.

When we got into the Thames and were nearing the bridges we would lower

the masts, then stand by to lower the funnel as we came to each bridge,

then let the counter-balance weight pull it up to its normal position when

we came out on the other side. This was a coal burning steam ship, so you

can imagine what it was like standing in a cloud of smoke and steam as we

passed under each bridge on our way to Fulham gasworks or Woolwich power

station.

One of the lads on this ship had been one of Carol Levis’ Discoveries on

the radio before the war, and when he heard about my attempts to play the

accordion he told me to bring it aboard on the next trip and he would try

to teach me how to play the left hand. Part of his act had involved

playing the accordion. After several weeks of coaching I finally managed

to play a very basic left hand to go with my attempts on the right hand,

but I would not like to inflict my “music” on an audience.

The war was over so we did not have to fear being attacked by enemy planes

or submarines but had to keep very carefully to the clear channels through

the minefields. There was the ever present danger of mines breaking adrift

from their moorings and occasionally one was spotted and had to be

reported to the Admiralty so that they could deal with it.

After some fairly humdrum trips we docked in Hartlepool at about tea time

on Christmas Eve and thought “Great, we will be home for Christmas”, as

the dockers would surely not load us on Christmas Day, but no such luck.

We got telegrams telling us to report on board at noon on Christmas Day to

sail at four pm. I was so browned off that when we were asked to sign on

for another six months on the ninth of January, I asked to leave and wait

for another ship.

BACK TO FOREIGN GOING

I joined the Chulmleigh on 29th January 1946 while she was fitting out at

Doxfords Shipyard.

As time went on, new ships were fitted with better accommodation for the

crew and this time we had a day room as well as a cabin between two men.

We did the usual sea trials for a new ship, then loaded coal for the

Bethlehem Steel works at Sparrows Point, Baltimore, USA. Then we sailed

for St John’s New Brunswick in Canada to load grain. It was very cold at

this time of the year and you had to be careful not to touch metal such as

the ship’s rails without gloves on or your hand would freeze to the metal

causing an ice burn. We were to take this cargo to Spillers Wharf at

Newcastle, which was to all intents and purposes a trip home. As we were