Edward Ford

/back

Service Record

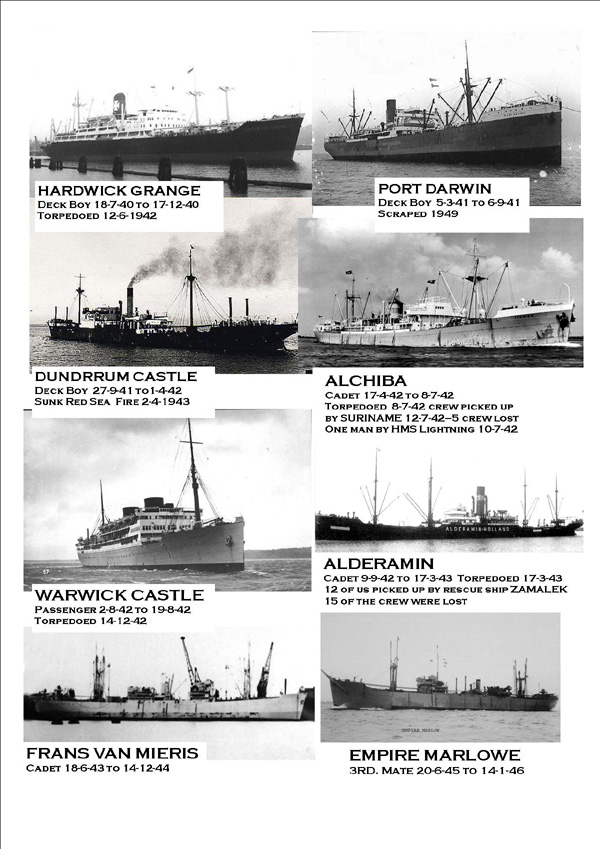

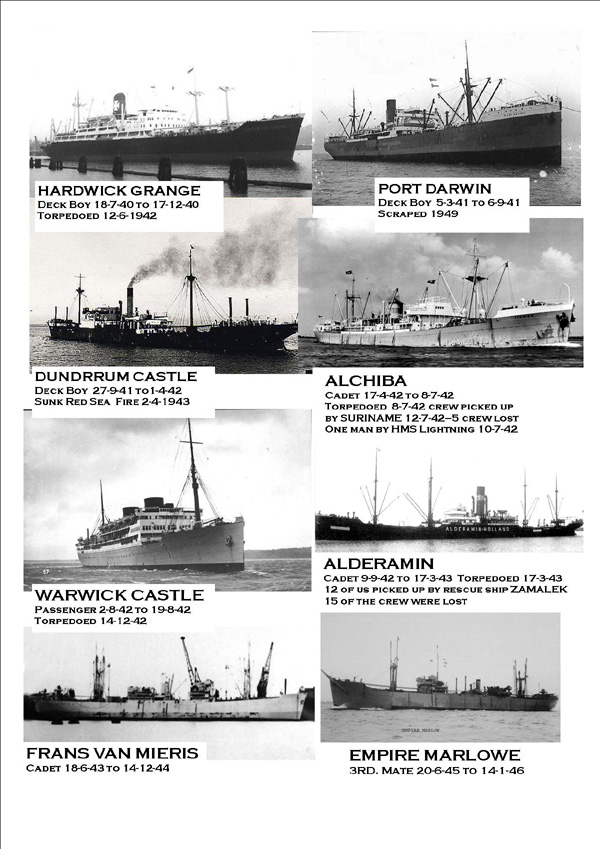

SS Hardwicke Grange

Deck Boy 18th. July 1940 to 17th. Dec. 1940

SS Port Darwin

Deck Boy 5th. March 1941 to 6th. Sept 1941

SS Dundrum Castle

Deck Boy 27th. Sept 1941 to 1st. Apr 1942

SS Alchiba

Cadet 17th. Apr 1942 to 8th. July 1942

SS Alderamin

Cadet 9th Sep 1942 17th. March 1943

SS Frans Van Mieris

Cadet 10th Jun 1943 to 24th. Dec 1944

SS Empire Marlowe

3rd. Mate 20th. Jun 1945 to 14th. Jan 1946

Forward: I would ask anyone reading the below

story to bear two things in mind:

(1) Dates given for joining and discharge from ships are correct I have

documents.

(2) All other information is as I remember it some 60 years later, I can but

hope that it is all correct. Where I have found other information since writing

I have tried to add it.

MY WAR 1939-1945

Forward:

I would ask anyone reading this to bear two things in mind.

Forward:

I would ask anyone reading this to bear two things in mind.

(1) Dates given for joining and discharge from ships are correct I have

documents.

(2) All other information is as I remember it some 60 years later, I can but

hope that it is all correct. Where I have found other information since writing

I have tried to add it.

Having left school at the start of the summer holidays in 1939, the war

likely at any time I moved to Cambridge to wait for the war to start. Joe

Tomlinson, an old family friend was with British Sailors Society and was

arranging for me to have a place at the Prince of Wales Sea Training Hostel, but

as the school was moving from the London East End docks to Ingham in Norfolk I

had to wait until October (a ? has been put on this date I would like to know

where I was Christmas 1939) to take up my place at the school.

Life at the school was something new to me, I had never lived away from home and

here I was with other boys from all over the country all with a different way of

talking, one lad from Glasgow ( could this have been Angus Robertson) I could

not understand. Ingham Old Hall was now the home of the school, our boats had

been moved up to the Norfolk Broads or so we were told as I never saw them all

the time I was there. The sleeping was in bunk beds in dormitories twelve to a

room, all the cleaning was done by the boys and one spent a week at a time on

each job. If your job was not done to the satisfaction of the officer of the

watch then you did a second week, this seemed only to apply to jobs nobody

wanted to do. Laundry you had to do your own and time was set aside for the

purpose, the day was governed by the ships bell and was divided into watches. We

had instruction in seamanship, sail making, rope work, Morse code and semaphore.

With the signalling I needed someone to write the letters down as I called them

out, I was unable to make words in my head out of the letters flashed at me.

Life at the school was good as long as you ate what was given, there was enough

to eat, as long as you were not too fussy. Saturday and Sunday afternoons we

were able to go out and the school had some bicycles we could use otherwise it

was walking every were.

Sunday mornings we had Church Parade when we marched in our best uniforms with

the officers leading to Stalham 2 miles away, those wishing to go to the

Catholic or Methodist Churches were allowed to leave the march as we passed

them. When we were out from the school we had to be in uniform so at all times

and had to behave ourselves as there were only about 40 of us so any wrong doing

would soon get back to the school. My time at the school was very enjoyable for

most of the time I liked the things we were doing. No English or spelling (apart

from signalling) even so I managed to get my signaller's badge. Owing to being

sick for a month with an infected ankle one week in the Norfolk & Norwich

hospital and three in the sick bay, I did not complete the course till the end

of June 1940, by which time France had fallen and a lot of our forces were

evacuated from Dunkerque. Apart from the RAF our defences were non-existent. On

the Norfolk coast at Sea Palling the Coast Guard had one rifle between three of

them and that was one left over from the First World War. The beach was not

protected in any way and we used to walk down to the Coast Guard station on a

Sunday afternoon and talk to the one on duty. At this time I was asked if I

wished to give up the idea of going to sea until after the war was over but as

there was nothing else I wished to do I said no.

After a short holiday with Gran in Cambridge I joined my first ship The

Hardwicke Grange 9005 tons gross on the 18th. July 1940. (she was torpedoed

12th. June 1942).

The ship

belonged to Holder Brothers and was on the South American meat run, she served

as an armed merchant cruiser in the first world war and still had the six inch

gun mountings but only one gun mounted on the stern platform. Apart from the 78

members of the ships crew there were two RN gunners whose job it was to look

after the 6” gun, depth charges, Lewis guns and train members of the ships crew

to man the six inch gun. Having a speed of 14 knots we sailed independently of

convoys, this ship was the only oil burning ship I served on for my whole time

at sea. At the age of 15 my position was right at the bottom of the seaman’s

ladder, with the title of Deck Boy or known on board as Peggy. The working week

was 72 hours with days of leaving and arriving in port 12 hours, all for

£3-15s-0d a month and £5 a month war bonus. The only ones paid less were the

Apprentices they got £10 a year the first year increasing by £5 a year for 4

years, to be an apprentice you had to be 16 and have your school

matriculation.

The deck crew consisted

of: The bosun, Bosun’s mate, 3 Quarter masters, 6 able seaman, 3 ordinary seaman

and 2 deck boys. Work was arranged in 3 watches 8-12, 12-4 and 4-8 each watch

had 1 QM, 1 AB, & 1 OS the rest were on day work. The three members of the

watch shared the duties of helmsman and look out, the QM doing 3 hours helm and

one hours stand by, the AB one hours helm one stand by and two hours look out

and the OS three hours look out and one hour stand by. When on stand by during

day light they were expected to join the day workers. The work of the day

workers was ships maintenance, my job as Peggy was to look after the seaman’s

mess collect the food from the galley the rations tea, coffee, butter, sugar,

etc. The laundry, sheets, etc. from the purser, clean linen was given out once a

week. Other times I would be working on deck with the day workers, the good

times were when I was able to take the helm under the watchful eye of the

quarter master who would stand looking aft to check the wake was a nice straight

line. As luck would have it I seemed to be good at it so I was often up there to

release the AB for deck work. I did two trips to Rio De Janerio, Montevideo

and, Buenos Aires between 18-6-40 and 17-12-40. The Graf Spee had been scuttled

off Montevideo and its supply ship interned December 1939,all that could be seen

of the Graf Spee were the masts sticking out of the water. The end of a fine

ship. It was strange to meet up with the German crew in the bars on shore, we

seemed to accept each other as merchant seamen even though our countries were at

war. We docked in Glasgow after the first trip and were given three days leave

and a rail pass back to London. The blitz had been going for 47 days so after

spending three nights in the shelter I was please to catch the train back to

Glasgow, much more peaceful at sea. We returned to Glasgow after the second and

uneventful voyage and the ship paid off so I was off home for Christmas complete

with ration card and a box of kippers. That was to be my last Christmas at home

till 1944 when I arrived home on Christmas eve.

I was at home all of

January (I was still only 15 so could still please myself) and went to Liverpool

at the end of the month to find another ship, this turned out to be a wait of a

month. The time was spent living in the seaman’s hostel with a daily call at the

shipping office, the rest of the time on the snooker tables. On the 5th.

March 1941 I joined the Port Darwin (The photo is of

the Port Denison her sister ship the Port Darwin survived the war and was

scraped in 1949)

Still as a Deck Boy it seems that I could not

be an Ordinary Seaman till I was 17. Again it was a refrigerated ship, smaller

than the Hardwicke Grange and coal burning with a maximum speed of 12 knots. The

fridge engines were larger than the main engines. We left Liverpool in convoy

but after two days left and made our way to Boston where we took on a cargo of

steel bars and case oil (50 gal drums of oil ) and made our down to the Panama

Cannel. The Cannel was under the control of the USA and we had armed guards on

board all the way through. The trip through the cannel was interesting at times

sailing through dense rain forest a ship looking well out of place, the only

passing places being in the lakes in the middle (since that time the cannel has

been widened and ships can pass in the cuttings). Once through the cannel we

took on coal and water and set off for Australia on what turned out to be the

longest sea passage I was ever to make without seeing another vessel, 30 days on

a sea like a mill pond and bright sunshine all the way. About 10 days out from

Panama a fire was found in the bunkers and all the coal had to be got out and

brought up on deck to get to the seat of the fire so that it could be put out.

At times like this it is a case of all hands to work and no overtime, it goes

down to the safety of the ship and the lives aboard it.

We spent the next few weeks discharging our cargo in Brisbane, Sydney and

Melbourne and then made our way to Auckland to load up with lamb and head for

home via Panama arriving back in the UK on the 6-9-41 after an uneventful voyage

when the ship paid off and I was once again on leave . I was only home for three

weeks before I was off to sea again still as a deck boy. I joined the Dundrum

Castle (she caught fire and sank in the Red sea 2nd.April 1943)

An old tramp of the Union Castle Line only

5,000 tons with a maximum speed of 7 knots, with each ship I seemed to be going

down hill and I was beginning to think that I would soon have to do something

about it. Anyway we loaded up with war supplies and set off in convoy bound for

Bombay after a week the convoy broke up and we headed for Cape Town on our own.

All went well until we received a raider warning and headed for the west African

coast at all possible speed , the poor ship nearly fell apart and somehow

managed 8 knots. We reached Walvis Bay in South West Africa and stayed there for

a week until the German Raider had moved to another part of the Atlantic. From

there we went to Cape Town and then onto Durban where we refilled our bunkers

with coal before setting off for Bombay. After unloading we set off for Port

Louis Mauritius where we loaded sugar before going back to Durban for Coal,

water and stores after which we headed for home arriving back after an

uneventful voyage on the 1-4-42 when the ship paid off and I was once again on

leave.

I stayed in London for this leave as I was determined that my time as a deck boy

was over and looked round for a way to change things. My first call was back to

the British Sailor’s Society as I was a member of the old boys association from

sea school days. I am pleased to say it worked and they found me a position with

the Netherlands Shipping and Trading Committee who had taken over the management

of all the Dutch ships sailing out of the UK.

On the 17th. April 1942 I went to Hull and joined the Alchiba as a Cadet, at

last I would learn the things that mattered, I had arranged a correspondence

course with the King Edward 7th. Nautical Collage and armed myself with all the

books and a sextant I was on my way. I was the only Cadet on board with only one

other Englishman, the Radio operator, it turned out to be a happy ship with all

the crew being able to speak English. When in port I worked with the carpenter

and at sea kept watch with the Chief Mate. We loaded with supplies for our

forces in India around 5000 tuns of ammunition and other hardware with two RAF

air sea rescue launches as deck cargo. So we set off for Bombay thinking that we

should be issued with parachutes not life jackets. We made our way up the east

coast in convoy to go north about to Lock Long where we waited for a convoy to

head south, a week out we left the convoy and headed for Durban to take on coal.

We set sail from Durban on the evening of the 5th. July heading north through

the Mozambique Channel, three days later while walking round the ship checking

the blackout we were hit by a torpedo in the only safe place the bunker which

had just been filled with coal. As we always traveled with the lifeboats swung

out the two boats on the port side were lost, the engine room was out of action.

I made my way back to the bridge to find it deserted, so made my way to the boat

deck and took up my position in the No.1 boat. All but 8 of the crew got away in

the two starboard boats, three launched a raft on the port side, the 5 in the

boiler room were lost. The No.1 boat had a single cylinder engine so we took the

other boat in tow and put as much distance as possible between us and the

submarine. (This I have found out since was Japanese I-10 Commander Nakajima

Seiji, He sank eight ships including us in June-July 1942).

The sub surfaced on the far side of the ship from us and started to shell her to

finish her off, but before she was hit she broke her back and sunk. From start

to finish was 15 minutes and we made our way in the dark hoping that the sub

would not come after us. That night we headed west towards the coast some 6oo

miles away with the other boat still on tow. The morning came and we were able

to take stock, the captain and first mate were in our boat ( the first mate’s

boat having been destroyed when the torpedo hit us ) so each boat had half the

survivors. The sea was like a millpond and the wind light to non-existent the

engine was now useless as the shaft gland was leaking when the engine was

running, so the tow was cast off and we set sail. This turned out to be the

first of four days spent in the boat, food and water were in short supply as the

boat had more people than was catered for and we had no idea how long it would

take us to reach land with the wind so light. Rations were quarter of a cup of

water a slice of corned beef and one biscuit twice a day. The days were hot and

the nights cold we were all in shorts and only a shirt on top. The morning of

the second day downed with no sight of the other boat, progress was very slow

with just the fin of a shark following the boat from time to time. On the

evening of the forth day we were sighted by another Dutch ship bound for Beira

in Portuguese East Africa and they stopped to pick us up, they had picked up the

other boat some hours before and were looking for us. That night we arrived off

Beira and in the morning the ship docked and we were put ashore, only to find

that being without papers as to identity we were placed in an internment camp.

The British Counsel arranged new papers for us and a week later we boarded a

train for Cape Town.

The word had gone before us and when we arrived at Bulawayo to change trains the

locals had turned out to see the survivors on there way to Cape Town. We had

three nights on the trains through all types of countryside, mountains and

dessert, at times they used two engines to pull us through the mountains. On the

forth day we arrived in Cape Town where we were put up in a hotel to wait for a

ship to take us home. We were given money and were able to kit ourselves out

again and life was very pleasant once again. The radio operator and I were given

passage on the Warwick.

She was a motor ship of some 17000 tons with a

speed of 20 knots, she had been converted to a troop ship and the first class

passenger accommodation had been converted to bunk beds. We had an uneventful

trip home and 17 days later we arrived back in the UK. So ended my first trip as

a Cadet with the Netherlands Shipping and Trading Committee (I have since found

out that she was torpedoed off Portugal on the 14th. November 1942)

After a short leave I returned to the shipping office from where I was sent to

join the S.S. Alderamin

in Liverpool on the 9/9/42. A ship of some 10,000 tons built in Germany in 1920

and given to the Dutch as reparations after the war. She was a strange looking

ship with four tall masts and a hull made of inch thick steel plates with a

maximum speed of 9 ½ knots.

Loaded with supplies for the army we set off in convoy bound for west Africa,

three days out we left the convoy and made our way to Free Town where we

unloaded. This took some time as all the unloading was into barges and done with

our own derricks but in the end the job was done and we set off down the coast

to Lagos where we were to load peanuts. This port and loading had to be seen to

be believed, there was a long wharf on the mouth of the river, with the Navel

anchorage about ½ a mile inland then further up stream was a ship repair yard

and above that was an oil terminal. The method of loading must have dated back

to the days of sailing ships when only a few hundred tons were loaded at a time.

Two gangways were placed to the fore deck and two aft, then there was a

continuous stream of men with a sack of nuts on their backs running up one

gangway tipping the contents down the hold and taking the empty sack down the

other. The process was continuous, I think they were paid by the number of sacks

they did in a day as they were running all the time.

Disaster came one day in the form of a fire, we had been smelling oil all

morning it seems that there was a leek from the oil terminal. How the fire

started I don’t know but from the repair yard down to the Navel anchorage the

river was one mass of flame all the men loading us disappeared the moment the

fire started, one moment our deck was crowded and the next empty. There were

three minesweepers in the anchorage that were engulfed in the fire when the

depth charges exploded and put out the fire and the three ships, the anchorage

was empty. We were able to get two survivors from the sweepers, they had jumped

overboard before the fire had reached them, only to be put on a charge for

abandoning ship before being ordered. We completed our loading around 8,000 tons

of peanuts all loose in the holds, and went to the coal wharf to top up our

bunkers. Just before Christmas we set sail for home with orders to go to Port of

Spain in Trinidad to join a convoy to New York before joining a convoy across

the Atlantic and home. We spent Christmas and New Year zig zaging our way across

the ocean to miss the radio reports of submarines and putting out our second

bunker fire (the first being on the Port Darwin). We did arrive in Trinidad a

week late and missed the convoy north, so we spent the next two weeks being

entertained by the good people of the British Sailors Society. By the time we

got to New York it was February and there was a foot of ice on the Hudson River

and the Chief Engineer said there was trouble with the engine and we went into

Brooklyn dockyard. As the boilers were shut down we were all moved to a hotel in

New York, once again the club came up trumps so I took a weeks leave and went to

Bridgehamton Long Island to stay with the local people. All the houses were

wooden but one which was brick, one shop, one church and one policeman, I must

say they looked after me very well and was sorry when I had to go and rejoin my

ship.

We left New York the beginning of March 1943 in convoy for home, it seemed that

we had spent a lot of time getting nowhere at least now we were on our way home

albeit at 5 knots. The weather was bad from day one with gale force winds and

cold, ice forming on the ships rails, it needs to be cold for salt water to

freeze. From the bridge 40 foot above the water line one looked up at the crest

of the waves. We were having trouble keeping station the convoy speed was too

slow to keep a good course and it was just possible to see the faint blue light

on the ship in front. The last thing on our minds was the possibility of a

submarine being able to operate in the conditions at the time. On the 16th.March

I was on the 8 to 12 watch with the 3rd.Mate 8 bells had gone for midnight. My

relief had not turned up and after 4 hours out in the cold I was not pleased,

but then who knows why things happen. At 5 passed he turned up and 5 minutes

later when I had handed over to him I was about to go below when the torpedo hit

us. Five ships were hit in fewer minutes, how they managed to operate I don’t

know we were three rows in and three down. 17 of us left the ship in number one

boat but it turned out to be damaged and filled with water after some time we

drifted against an empty life raft witch we managed to get hold of. The 12 of us

that were able got on to the raft so we were able to sit with our legs out of

the water, the 5 that were left in the boat were believed to be dead. Just after

5 in the morning we were picked up by the rescue ship attached to the convoy,

another hour or so would have finished the rest of us off.

The rescue ship was

only 1.500 tons and had started life as a passenger ship in the Mediterranean

and life in a 40ft. Swell was not very pleasant. We were found dry clothes to

put on and a bunk to sleep on, the ship was crowded, cold and wet but after some

hot food we went to sleep. We spent the next week being tossed around with the

little ship climbing up one side of the swell to have the propeller out of the

water racing like mad before rushing down the other side. We spent the whole of

the time below decks without news of what was going on outside, I have no idea

of how many more ships were lost on the way home but our numbers down below did

increase. We arrived in Glasgow and were put ashore with £5, a travel warrant to

London, and a piece of paper stating “Mr. Ford states that he is a British

subject and is permitted to land in the UK”. So I headed for London and the

shipping office only to be sent off to the Royal Free Hospital with a letter to

get my legs sorted out. This was the start of weeks at the out patients

department with my legs in metal knee boots filled with salt water and an

electric current passed through them. I insert hear some research done by Stuhogg an ex Prince of Wales School Boy. To him I offer my thanks for his

research.

March 16 -19 1943German Radio called it "Greatest Convoy Battle of all Time."

Convoys SC122 and HX229. 16-19 March 1943.

Introduction.

Convoys SC122, and HX 229 sailed to the UK shortly after each other in March of

1943, with an entirely inadequate escort. Strung out ahead in the North Atlantic

three packs of U-Boats were waiting. Some 40 boats in all. In the coming

slaughter, 22 Allied ships were sunk for the loss of but one U-Boat, U-344.

Slow Convoy SC122.

This convoy sailed out of New York on the 5th. of March 1943 and it almost

immediately ran into a gale, which slowed it even more.

The 9th. of March found a feeder convoy consisting of 14 ships ex Halifax

joining up, it included the rescue ship HMS Zamelek, making an amazing 18th.

voyage in that role. She must have led a charmed life to chug back and forth

across the North Atlantic in that unenvious task of dropping back out of the

bosom of a convoy to be alone, to stop, and pick up stranded sailors from a

torpedoed ship whilst a sitting duck. With additions this convoy now numbered 50

ships, 5 for Iceland, the remainder destined for the British Isles, all laden

with cargoes desperately awaited at their final port.

Three U-Boat packs sit in wait.

Allied intelligence on the 12th. of March read a message from U-621. Convoy

SC122, was ordered to alter course southward to slip past the waiting Raubgraf

(Robber Baron) wolf pack. This was successful, but the two other groups still

lay in the path of SC122, with Sturmer (Dare Devil) with 18 boats, and south of

them Dranger, (Harrier) with their 11 boats. A further 4 submarines were not

assigned to a particular pack. Danger was in the offing!

Allied Control was unaware of the other two wolf packs lying in wait for

SC122.

Fast Convoy Halifax229 sailed from New York on the 11th. of March with 40 ships.

A second segment, HX229A, sailed from New York on the 12th. of March, 28 ships,

4 for Halifax, with a local escort of 5 vessels. Another 16 ships, ex Halifax

joined up with 229A.

We now have 3 convoys all eastbound, with SC122 in the van but moving at about 7

knots. On the 15th. of March it ran slap bang into another serious gale.

Commanded by Heinz Walkerling, U-91 found what he thought was SC122 on the 15th.

of March, but in fact he had picked up Halifax 229, it was overtaking the

plodding SC122.

3 Raubgraf boats, U-84, U-664, and U-758 were ordered by their German Control to

close on U-91.

Whilst looking for his U-Boat tanker, Gerhard Feiler in U-653 ,who was on his

way home, ran into an eastbound convoy, he thought he had come across SC122, but

no, he too had found the fast and overtaking HX229.

Control now ordered 2 boats just refueled from tanker boats, the remaining 9

from Raubgraf, 11 from Sturmer, and a further 6 from Dranger, and 11 others to

speed to the west and close on Feiler. We now have 38 U-boats on their way to

join U-653.

Carnage looked highly likely.

Over the 16th./17th. of March, 8 U-Boats fell upon HX229, but thought they were

onto SC122.

The battle continued, Heinz Walkerling in U-91, polished off the 6,400 ton

American Harry Luckenbach, and proceeded to have a picnic, picking off the 4

damaged ships, James Ogelthorpe, Nariva, Irenee Du Pont and William Eustis.

Still the sinkings went on apace, U-384 sank the British 7,200 ton Coracero, and

it finally finished when Jurgen Krugrer in his U-631 sank the Dutch freighter

Terkoelei of 5,200 tons.

All in all, 10 ships totaling 72,000 tons were sunk, 7 different U-Boats had

enjoyed success.

It was a terrible error in not ensuring that a rescue ship sailed with HX 229,

it turned out that only 2 of the escorts stayed with the convoy, whist the rest

were kept busy trying to pick up survivors from the 10 sunken ships.

Now it was SC 122's turn to be attacked.

But the Sturmer and Dranger boats were off to the west at high speed, and on the

night of the 16th. /17th. of March, Manfred Kinzel in his brand new U-338 at

last found SC122. He avoided the escort to fire 5 torpedoes into the heart of

the convoy, he sank 2 British freighters, Kingsbury, and King Gruffydd, the

Dutch 7,900 ton Alderamin, and damaged the 7,200 ton Britisher Fort Cedar Lake,

a stunning result for his 5 fish.

HMS Zamelek the Rescue Ship screened by the corvette HMS Saxifrage, dropped back

to cope with the mass of survivors.

U-Boat Control were confused, they thought the first attack was on SC122, and

this one on HX229 , in fact it was the other way round.

The Escort Commander, Richard Boyle, asked for reinforcements from Iceland, plus

some heavy air cover.

At last, very long range B-24's (Liberators) from British Squadrons 120, in

Reykjavik, Iceland, and 86, in Aldergrove, Northern Ireland gave air cover both

in the morning and afternoon of the 17th. of March .

With the dawn of the 18th. of March both SC122 and HX229 were about 250/300 mile

from Iceland. The 19th. of March found Coastal Command mounting the largest air

cover yet provided for a North Atlantic convoy, B-24's, B-17's and Sunderlands

all played their part.

In Berlin, the propagandists tended to lump SC122 and HX229 as one battle,

rather than two separate fights, they claimed 38/40 U-Boats had sunk up to 32

enemy ships adding to 186,000 tons, the greatest ever success against a convoy.

SC122 lost 9 ships, and HX229 13 vessels, all up, 146,500 tons, and 40 U -boats

committed. This result, a little over half a ship sunk per U-Boat involved, was

about average , none the less, the Allies could ill afford to lose them.

Conclusion.

22 ships sunk was a great result for Donitz's U-Boat arm. On the Escort front,

both convoys were denied serious escort protection. The whole scenario was only

saved from being a total disaster by the air umbrella flown by Very Long Range

B-24's, B-17's and Sunderlands which forced the U-Boats to keep their heads

down.

The 10 days without U-Boat signal traffic intelligence proved very costly, 22

ships sunk, crewmen dying, and their precious cargoes destroyed. By the 20th. of

March 1943, all the U-Boat traffic was again being read.

These two convoys indicated the necessity of strong ship escorts, and of heavy

air cover. But in only two more months the Allies were on top of the U-Boat

menace on the Atlantic run. In May of 1943, The Battle of the Atlantic was

finally won and Uboats were no longer able to hunt in packs. The master of the SS

Alderamin, Captain Van Os, was picked up by HMS Saxifrage, a Royal Navy

corvette. Captain Van Os was later the master of the SS Alpherat when she was

attacked and sunk east of Malta, 21 December 1943. By very strange coincidence

he was again rescued by HMS Saxifrage.

The following I found as conformation of the fire at Lagos. The only difference

is oil and petrol.

PETROL SPILL

On December 5, 1942, three naval trawlers, commissioned as anti-submarine

warfare vessels, HMS Canna, HMS Bengali and HMS Spaniard were berthed in the

harbour at Lagos when a petrol spill caught fire engulfing the three ships. One

by one they exploded and in the process killed around 200 people. Fishing

trawlers were used extensively during the war on escort duties and mine

sweeping.

By the start of June I was fed up going to the hospital with no improvement

with my legs I went back to the shipping office and asked to return to sea in

hopes that the return to wormier weather would do me more good. They did suggest

that as I had lost the first two of their ships that I had sailed on putting me

on a third might not be a good idea. Never the less I was soon of to Liverpool

where I joined the Frans Ven Mieris on the 10th. June 1943, this was a wartime

built ship of the Empire class, coal fired with a speed of 9 knots around 8,000

tons, a new ship on her maiden voyage. We were loaded with army stores of all

types plus a deck cargo of vehicles and one landing craft and its crew, one RN

midshipman, one AB and one engineer. We left Liverpool not knowing where we were

going but with orders to join the convoy forming up outside, then we headed

south into wormier weather though it was still painful to stand for a long time,

things were a little better.

As we sailed further south the watch system changed and we went to 6 hours on

and 6 off, when there was a submarine alert every one was on. We had three days

of a constant alert at the time I wondered what good we were all doing as it was

a job to keep one’s eyes open. After a day without an alert we headed east for

the straight of Gibraltar so at last we knew where we were going. All went well

until one night we found ourselves in the middle of a convoy coming out from

Gibraltar. How the escorts passed each other I don’t know but ships started

putting their navigation lights on and the two convoys were amongst each other,

fun and games until the convoys got on opposite courses. We arrived at the

beachhead on the southern part of Sicily the day after the landing to a very

quiet scene and spent the next week unloading without interruption.

After we left the beach head we went to Bizerte to join a hundred or more other

ships waiting to load for the next beach head. We were all at anchor in the Lake

of Bizerte with very little to do other than anchor watches, and general

maintenance duties. I spent my time between watch keeping and updating the

sailing directions from the “Notice to Mariners” These were books that contained

information on all ports and coastline round the world. The weather was fine and

the water in the lake was clear, it was possible to see the bottom some 50ft.

below. In all we spent three months there, with no shore leave and only two air

raids when every ship was letting go with everything they had, none of the ships

were damaged in any way.

The day came when we took on coal and water and were given orders to go to

Skikda in Algeria to take on cargo and await orders. Skikda was a small port run

by the US army, we set about loading general stores and ammunition, complete

with field guns and Jeeps to tow them plus a large amount of jerry cans full of

petrol. We were two weeks loading and were able to get ashore when we were not

on duty. It was while we were at Skikda that we were able to make two trips to

Constantine some 60Km inland, the US army was running lorries to and from

Constantine all day and night so it was easy to get a lift but the roads made

the trip a nightmare. Constantine it self was on the top of a hill with a deep

narrow gorge running through it, an interesting place and well worth a visit. I

believe that it is now called Qacentina.

After loading we joined a convoy heading north and arrived at the Salerno beach

head two days after the landing, we anchored and started unloading into large

landing craft our own small craft was also being used. It was a hard fight when

the troops first went ashore and the losses were great as the Germans were

waiting for them. The anchorage was quiet, apart from a railway gun on the

mountain to the north of us which came out of a tunnel to send a few shells at

the ships only to have the navy fire back and drive them back into their tunnel.

This happened once or twice a day all the time we were there, all they ever hit

was one landing craft. When we had completed unloading we left the anchorage and

headed south, leaving our landing craft and its crew behind to work with the

ships that remained. Our next stop was Catania on the east coast of Sicily where

we took on ships stores and I went into the 66th. Army hospital with a tummy

bug, as the hospital was full of the wounded from the Salerno landing the next

day I asked to return to the ship I felt most uncomfortable with so many badly

wounded there. I got back to the ship just in time as we sailed that night for

Algiers.

We had a few air raids while we were there but no damage was done to any of the

ships only one bomb dropped on the wharf. It was while we were there that Italy

surrendered, the Germans were still fighting in the northern part of Italy so we

loaded with supplies for the army and sailed for Bari on the East coast of

Italy. We arrived to find a lot of damage but no blackout all the lights were on

in the town and they were acting as if the war was over. We were allowed ashore

for the second time since joining to ship (not counting my hospital visit). The

damage ashore was extensive, the Italian police were about still armed and a few

old people looking very dejected, otherwise it was as if the place was deserted.

We completed our unloading and went off to Haifa to load oranges. No shore

leave. We set off for home having completed loading the beginning of December

only to find westerly gales all through Mediterranean, we arrived at Gibraltar

to find that we had missed the convoy home by a week and would have to wait for

the next one. We were confined to the ship for our stay so the days passed with

anchor watches until we sailed for home, to arrive on Christmas eve with our

oranges unfit for sale as we had taken too long to get them home. This was the

end of my time with The Netherlands Ministry Shipping & Fisheries and I said

good bye on the 5th. February and joined the British pool.

Now it was back to school in the form of The King Edward VII Nautical Collage

down the east end of London, the course was to last three months after which I

would sit my 2nd. Mates exam. So started my daily trip from Norbury to London

Bridge station and from there by bus to the East End. This was the time that set

the course for the rest of my life. In the morning I had a two mile walk to

Norbury station. Where I get into the same compartment in the same carriage on

the same train seeing the same people every day, on arrival at London Bridge

there was a mad rush to the bus stop to get on the first bus and not have to

wait for the second one. Seeing the same faces every day Good Mornings were in

order and this was how I met the one that was to change my way of life.

It was hear that my wife to be first said good morning, I had been hoping for

some time that she would talk to me. From that time on we meet on the train each

day and traveled on the bus together, this continued until my course was over.

On the week of V.E. day I sat my 2nd. Mate’s exams, I passed the written parts

which lasted three days and orals but failed the signals, I was told to re-sit

the signals in six months time. So it was back to sea again. A visit to the

shipping pool found me a birth as third mate on the Empire Marlowe the ship was

at Ismailia and we were due to replace all the ships officers, so we signed on

for the usual six month – two year contract. Love is a strange thing and at the

time I did not like the idea of being away for up to two years and not knowing

if Eveline would still be there when I got back again. The safest way I could

think of was to ask her to marry me, this was 1945 I had just turned twenty and

Eveline would not be eighteen until the August. After some time her mother and

farther agreed as we would not be getting married for at least two years, so all

lose ends tied up I boarded an American troop ship bound for Alexandra. This was

how I arrived back in the land where I was born twenty years before. From

Alexandra it was a train to Ismailia where I set eyes on my new home, a coal

burning steam ship of 4,841 net tons with a speed of 8 ½ knots. The crew were

mainly Lascars with only the ten officers from the UK, the Captain, three Mates,

four engineers, Chief Steward and the Radio operator. The following day we

sailed for Durban to take on a cargo of coal to bring back to the Middle East.

At Durban they are able to load coal at the rate o 1,000 tons an hour so we were

only there for 24 hours, and we were on our way back to Port Side. Coal is one

of the most dangerous cargoes to carry as it can self ignite as I knew having

experienced two bunker fires in the past, thermometers were kept in pipes in all

the holds and the temperature taken twice a day and a log kept. The trip to Port

Side was uneventful with me getting used to being a watch keeping officer,

albeit that I was under orders to call the Captain if there were any changes of

any kind. This was peace time and time was money and we spent the next three

weeks unloading the coal with the ships derricks bringing the coal up in

baskets, to be carried to the barges by the Dockers. This meant that there was

coal dust everywhere, keeping the portholes closed and curtains over the

doorways did not keep it out. I did have the odd day off while I was there and

was able to visit the town of my birth (Cairo) and visit some old friends of my

Father’s. We were able to have a quick visit to the Pyramids and a look round

the town. I met many people in Port Side who remembered my Grandfather from his

days with the Ports & Lights of Egypt. I also managed to get in a visit to

Ismailia to see Joe Tomlinson who was stationed there with the Royal Navy, his

wife was left to run the British Sailors Society Home in Port Side which was his

peace time job. Joe was the one that arranged my place at the Prince of Wales

Sea Training Hostel, which was run by the B.S.S. From Port Side we went to

Naples to discharge more coal, it was on the way to Naples that I found myself

at odds with the idea that when the Captain was on the bridge he would give any

orders that were necessary, I was wrong in this case with this Captain. We were

making our way north through the straits of Messina at 2knots ( our water

injection pump had broken down so we had to reduce our use of steam) we had two

red lights hoisted on the signal halyard ( vessel not under command keep clear

of me ).

There was a mine field marked on the chart on our port side with a

swept channel from the port of Messina along witch a passenger ship was coming.

Now one thing is certain if the bearing of an approaching ship does not change

they will end up hitting each other. Now even without our two red lights it was

his duty to keep clear of us (our port side was on his starboard side). The

Captain had been on the bridge with me for some time nattering as he did about

the Pickwick Papers (he was well past retiring age) and we had been watching

this ship for half an hour or moor getting closer with me thinking that he

should be doing something about it, when I gave up and gave our horn two short

and one long blast (you are standing into danger) and had the wheel put hard to

starboard, it did wake them up and they passed astern of us just. The Captain

turned to me and said “left it a bit late didn’t you Mr. Ford”. I wonder to this

day what was going through his mind all the time the ship was getting nearer.

The rest of the journey to Naples was uneventful were we discharged more of our

coal. It was at Naples that our orders changed, a new captain was sent out to us

as the company was to take over the ownership from the ministry of transport, up

to now they had been managing it. Our new master was taking up his first command

and set about letting us all know it. We left Naples a few days later for Cagliara in Sardinia to unload the last of our coal. This was our last port of

call so when the unloading was completed it was clean up ship, at last the end

of coal dust everywhere and head for home. The company required the ship back

home for the hand over, the new captain changed the running of the ship

completely he did not trust anybody even the first mate had to call him if the

wind changed or another ship was sighted, he seemed frightened to go to sleep in

case something happened that he didn’t know about. The saving grace was that our

two year trip was going to be over in six months and we were on our way home,

next stop Manchester where we arrived on the 13th. January, I left the ship on

the 14th. and headed for home. I had spent six years of my life as sea lost two

ships and still had trouble with my legs also being engaged to Eveline I had no

desire to go back to sea again, apart from the fact that I was having trouble

with double vision. In March I went back to the shipping pool where I was given

an eye test and my discharge from the Merchant Service, with eye sight below the

standard required, so ended my days at sea.

Forward:

I would ask anyone reading this to bear two things in mind.

Forward:

I would ask anyone reading this to bear two things in mind.